Red

Here is the beginning of the latest essay I'm writing, based on our Christmas vacation.

**

Red

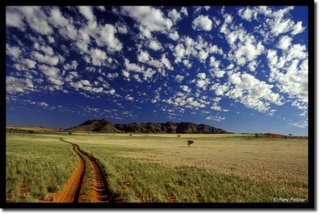

We are sliding along the Arizona floor slack-jawed and wide-eyed. Over us towers the Sedona rocks lifting from the desert in a rusty red so vibrant it glows. About two-thirds of the way up, the mountains instantly turn white. They jump from one color to the next like a line crossed. Over these two colors, along the cracks and creases, green shrubs grow like kinky hair.

“No wonder the Indians worshipped the world around them,” my mother says from the back seat. We hum a “yes” hardly able to speak, mesmerized by the red of this earth. And yet it isn’t quite red. The dirt glows with a color too orange to be red, too rusty to be orange, and too pink to be rust. It is the color of the terra cotta roofs that rise from the desert floor to form the city of Sedona. It is the color of clay lit with fire. And even along the edges of the rocks, if you look closely, you see that the color is changing in the present, every speck a different shade.

White bands run the mountains like wedding rings before conjealing at the peak in a bright crown of stone. Close to a crack over here the earth is a deep pink, then to the left it slips into a neon orange, and then further up it is suddenly neon rust. There’s no accounting for this active color which moves across the dirt, so long ago in order to simplify someone decided to call it “red.”

“It nearly takes your breath away,” my Dad says from the driver’s seat. We are on family vacation, spending Christmas at a Bed and Breakfast in Arizona, and we are spending the day driving to Sedona. When we reach the red city, we pile out of the car and into the bustle of strip malls and curio shops. We take lunch at the Vista Cantina and afterwards I stand outside the restaurant reading about the Sinagua Indians from a colorful poster. The last of their tribe left the Verde Valley in 1400 AD. There are several posters strung around the strip mall, each one relaying a different fact about the Sinagua culture.

The poster I’m reading shows a woman kneeling, a woven basket in her hands. She’s surrounded by a collection of desert vegetation: prickly pear cactus, acorns, and wild gourds. “The Sinagua were extremely successful farmers,” the poster reads, “harvesting a bounty of crops in the summer, and storing food for the winter.”

In the center of the strip mall, surrounded by a few trees, water, and stone is a bronze statue of two Sinagua Indians. A young man stands tall, his metal skin bare except for a piece of cloth against his thighs, and in front of him a young woman kneels. She has long hair that falls in smooth bronze over her shoulders and down her back. In her hands she holds a pitcher which pours and pours and pours a stream of water.

This land is chalked full of history and the whole state knows it. Everything from the local coffee shop cutely named “Shaw-nee Coffee” to the bronze statues at every hotel entrance and storefront, these people know how to draw us in. They flaunt a history we can not visit.

“I feel like I should see buffalo and cowboys,” Dwayne says holding his hand out to trace the mountains. He stops and smiles at me, “Or see a cowboy chasing an Indian, chasing a buffalo.” We chuckle and I put my arm around his waist.

In Prescott, an hour southwest of Sedona, we spend a day ducking in and out of novelty shops. Each one has a token picture of Geronimo, each one sells beads and dream catchers. One particular store is made of thick wood like a saloon, and behind a bar sits a wax Indian chief. Around his neck hangs a sign that says, “HOW! Would you like to sign up?” Something about a newsletter.

“What did Geronimo do?” my husband asks an old weathered store owner. He sits behind his wooden counter in a red plaid shirt.

“Well, he was an Indian chief” the owner says slowly, thinking about the question. “He didn’t like what was going on.”

“But what was he famous for?” Dwayne asks. I stand beside him curious on my own.

“Well, the Calvary hated him, chased him all over the states and down to Mexico.”

“Why do we say ‘Geronimo’ when we’re about to jump out of planes?” I ask.

“Well, I don’t really know about that” the owner says and our conversation stops. I’m left disappointed. Disappointed that this man who is packaging up the history of Arizona in cowboy hats, leather chaps, and a wax chief doesn’t know more about it. I'm also disappointed because all the paintings I’ve seen of beautiful dark skinned children wrapped in bright wool blankets with black hair blown against the red horizon leaves me wanting more. The statues and woven baskets and Native American trinkets are enough to evoke my curiosity, enough to convince me that there was beauty in the Native American way, but they point me nowhere, they lead me to emptiness.

It doesn't escape my attention that for all the bronze statues and paintings I have yet to see a single Native American in flesh walking through the streets of Prescott or Sedona. What if I want to go find these people? What if I want to spend a while observing the descedants of the Sinagua and Yavapai? Where do I go? They aren’t in Prescott. They’re not in the red hills where they began.

If I want to find any Native Americans at all, the internet tells me I need to go about seven miles west to the Yavapai-Prescott Indian Community in Prescott Valley, a reservation complete with shopping mall, resort, and casino. I go there. I eat dinner at "What-a-burger." I watch a movie at the Frontier Village. I visit the Prescott Resort and still I find no one with skin more red than mine.